Chokepoints

In military strategy and global trade, the chokepoint is one of the most interesting ways in which geography can be used to mess with the powers that be.

Billboard

Skyscrapper

Halfpage

In military strategy and global trade, the chokepoint is one of the most interesting ways in which geography can be used to mess with the powers that be.

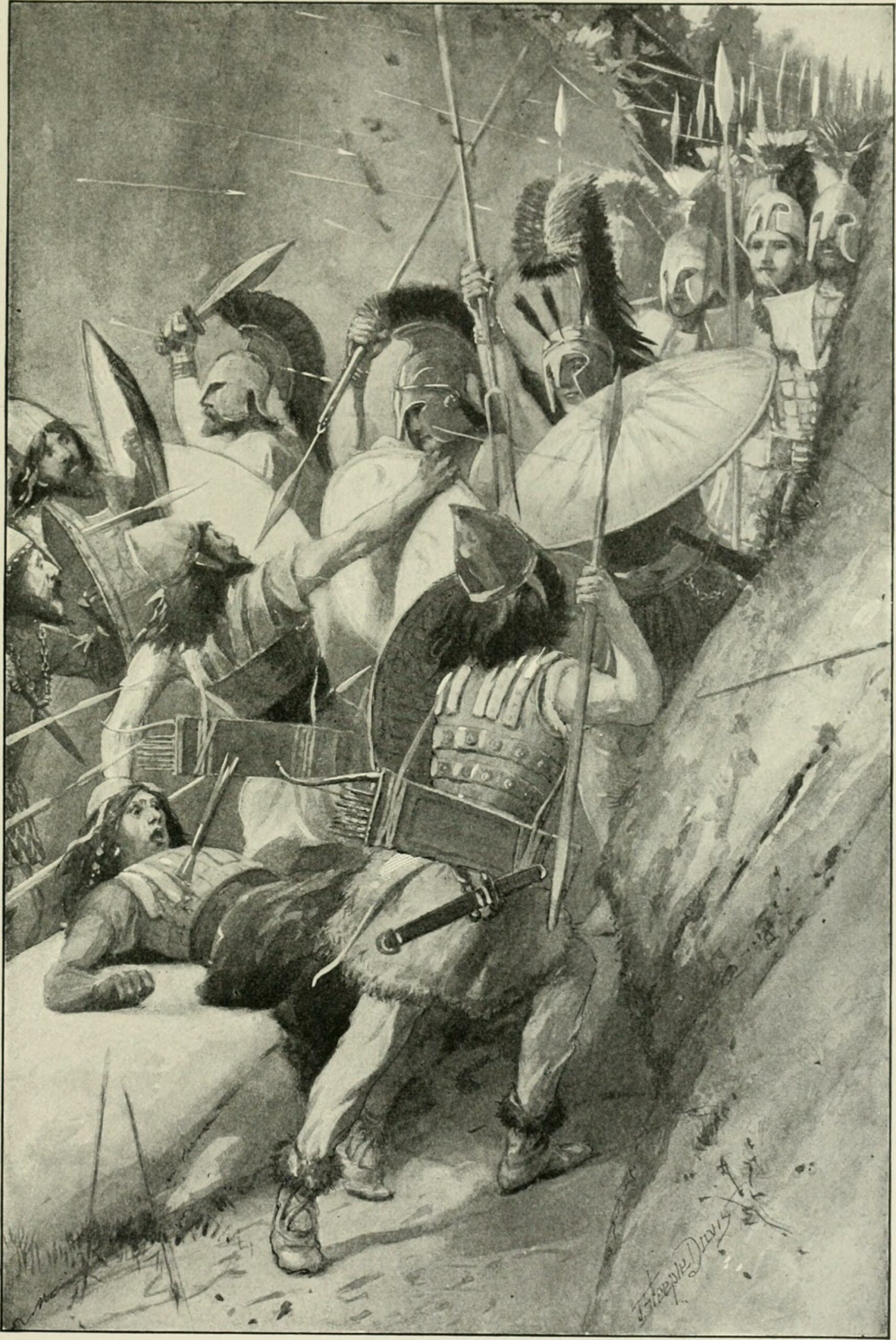

In the Ancient Battle of Thermopylae, a small army of 300 Spartans and 700 Thespians led by Spartan King Leonidas made a heroic last stand against the much larger army of Persian King Xerxes I. Though they were vastly outnumbered, the Greek forces were able to inflict heavy casualties on the Persian army through the effective use of the hoplite phalanx within the narrowest part of the Thermopylae Pass.

The Thermopylae Pass is perhaps the most famous example of a choke point, a geographical feature on land or at sea which an armed force is forced to pass at the risk of reducing their relative combat power against a numerically inferior opponent. In the case of Thermopylae, the choke point was a valley, but the term also traditionally describes straits or bridges. In the Battle of Stirling Bridge, for example, the Scottish forces led by William Wallace defeated a much larger English Army by luring the English forces across a narrow bridge.

From battles to trade – Chokepoints

From its original use as a term in military strategy, the choke point has evolved to describe a whole host of geopolitical features which act to limit the smooth flow of trade. This still includes areas of the map which are difficult to navigate. The Caribbean, for instance, was a popular place for pirates and buccaneers in the early stages of Western expansion into the Americas because the geography made it easy to ambush merchant ships. A similar problem is presented by the Strait of Hormuz, the entrance to the Persian Gulf, which receives 20% of the world’s oil traffic, making it an area of huge strategic importance to Western economies, and therefore, unsurprisingly, an area that has seen quite a lot of conflict over the last century. But the term also applies to aspects of various forms of transit. For instance, train lines can be major choke points since they confine goods to a fixed linear route for long distances, meaning that they are difficult both to maintain and defend and easy to sabotage. Similarly, busy seaports can be chokepoints due to the high concentration of goods flowing through them, which can often cause a bottleneck. It has also come to embrace more abstract geographical features, such as hard borders, protective tariffs and high concentrations of criminal enterprise, piracy, worker militancy or social movement activism.

To a certain extent, these last few “abstract” chokepoints all fall under the umbrella of national and local politics. Read in this way, they bring up an important (or, more specifically, fundamental) problem with our contemporary global economy. In this “just-in-time” or “lean” economy, time is of the essence: things need to move from place to place with minimal friction. If national and local politics are in opposition to this model, if they are seen to be “choking” the frictionless flow of commodities, then this model is in turn opposed to national and local politics (i.e. they’re opposed to popular democracy).

Brexit Chokepoints

This has been made starkly clear in the recent case of Brexit. Through its membership of the Single Market, the UK currently enjoys trade deals with 40 other countries. In the event of a No Deal, these agreements would disappear overnight. As Tom Kibasi, Director of the Institute for Public Policy Research, writes in a recent article for The Guardian, that would require “67 deals to be signed just to stand still.” Kibasi explains that the gravity of this scenario means it is unlikely to happen, but the very prospect of these new chokepoints emerging has already led major companies to move their operations elsewhere, including Nissan’s recent decision to move production of its new X-trail from its factory in Sunderland.

As this scenario illustrates, the fact that a democratic decision can act as such a major chokepoint should make us question how comfortable we are with subordinating everything to the smooth flow of trade.

Interestingly, if we want to challenge this state of affairs then one of the best ways is through these very chokepoints. For instance, the power that port workers, delivery drivers and other logistics workers have in slowing down or stopping the flow of trade, gives them enormous leverage in the global economy. Similarly, popular democracy, through its very control over the levers of national power, can also put checks on this flow. Read in this way, the chokepoint represented by the British people’s democratic power over a territory containing probably the most connected financial centre in the world, could be seen not as a risk but as an opportunity.